|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

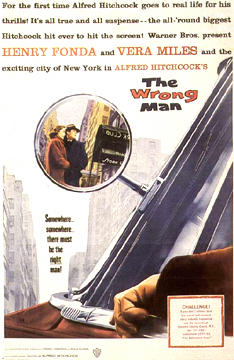

"The Wrong Man" (1956) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

Perhaps the most atypical of Alfred Hitchcock's dramatic films is the rarely screened THE WRONG MAN (Warner Bros.; 1956). It was based on a true story and was the last of Hitchcock's "experiments" in playing around with cinematic techniques. And in many ways the most successful. The innocent man wrongly accused of a crime is a well known theme of Hitchcock's and this story, which first appeared in a Life magazine article, naturally attracted his eye. A Stork Club bass player goes to an insurance office to see if he can borrow on his wife's policy and is mistaken for a man who had previously held up the place twice. There seems to be nothing that can prove his innocence, and his wife ultimately loses her sanity in the effort to do so. Only two irony quirks of fate save him. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

Hitchcock was determined to film this story as realistically as possible, on the actual locations in New York City and its environs where the events occurred. Yet, he could not resist applying his natural cinematic sensibilities to the project, and here, it offers a very interesting comparison to contemporary films. Although some critics and historians have called THE WRONG MAN a documentary or semi-documentary, Hitchcock felt he was still communicating a story to his audience, even if it was fact rather than fantasy based. The film's mise-en-scene (sic) is closer to the more reality based SHADOW OF A DOUBT (Universal; 1943) or I CONFESS (Warner Bros.; 1953), following the basic pattern set by Elia Kazan's all location BOOMERANG (20th Century-Fox; 1947), which, however, was told in a basically detached, straightforward manner. Hitchcock wanted to engage his audience in the drama cinematically, thus he sets up the ordinariness of Manny Balestrero's (Henry Fonda) life before his being picked up by the police, then details the procedure by which evidence is mounted against him, and his ultimate arrest and initial incarceration not in a series of dialog dominated master scenes, but with a multitude of shots of each activity, specifically designed and composed for maximum narrative and dramatic impact. This is a sharp contrast to the contemporary "faux documentary" technique of recording everything with gardenhosed handheld cameras. He was aided in this by his long time cinematographer Robert Burks, ASC, and art director Paul Sylbert. Given that these were the days of shooting with the old Mitchell BNCs, it would have been impossible to get the variety of setups and camera movements in actual interiors, especially the smaller ones, but Sylbert's sets have a natural aged look. (A hole in the plaster wall of the police interrogation room is given such a prominence that it would be interesting to find out if it was something Hitchcock asked for or an asset Sylbert gave him that he took advantage of!) He is helped in this by Burks, who photographed the sets as if they were actual locations, often even letting the highlights go hot as if he couldn't control them, as would have been the case on location in those days. He also appears to have shot most of the film on higher speed negative; the print shown recently at a LACMA Tuesday matinee was an original 1957 release print and then non-optical shots showed a degree of granularity not normally seen in Hollywood studio-shot films of the period. Given the obsessive use of handheld cameras these days, the POVs shot from a dollying camera now come off as a bit strange. Of course, the editing by George Tomasini is first rate, as is Bernard Herrmann's score, which is based around the bass violin that Manny plays, but also adds immeasurably to the film's basically downbeat mood. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

At a time when dramatic films seemed to have reverted to the pioneering sound days in which films were basically a series of acts of photographed plays photographed by multiple cameras, THE WRONG MAN would serve as a perfect example of how to tell a non-cinematic story cinematically; there are other good examples of course, including Rouben Mamoulian's pioneering sound film APPLAUSE (Paramount; 1929). It also presents another pro argument for the role of the director in the filmmaking process, that is, one who has a clear idea of how he or she wants to tell his story to the audience, the real secret of the success of most films considered great. For Hitchcock's practice of "creating" the film in the writing and pre-production phase of production, which some directors, especially those from an acting or theater background, claim to result in an ossified feel, has not hurt the spontaneity or quality of the film's performances. Indeed, the casting of little known supporting players enhances the film's reality. I had only seen this film once, thirty years ago, and was projecting it, so I couldn't give it the total attention I would have liked. Seeing it now, I feel that it truly deserves a higher status not only in the Hitchcock canon, but among all American films. |

|||||||

|

- Rick Mitchell

9 January 2007 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Back to Recommendations |

|||||||

|

Home / Hollywood Stories / Film Sound / Movie Props / Locations Trivia / Events / Tributes / Recommendations / Blog / About Bibliography / Links / FAQs / Shop / Message Board / Disclaimers / Site Map |

|||||||

Please support our site by visiting our affiliates: